Sisters in Innovation: 20 Women Inventors You Should Know / A Mighty Girl

How Many of These 20 Pioneering Female Inventors Did You Know?

Around the world and across history, innovative women have imagined, developed, tested, and perfected their creations, and yet most of us would be hard pressed to name even a single woman inventor. In fact, women inventors are behind many of the products and technologies used every day! From life rafts to disposable diapers to rocket fuel, women have invented amazing things — but they're also responsible for some of the things we use for day to day life. In fact, if you use GPS on your cell phone, turn on windshield wipers when you drive in the rain, or eat a chocolate chip cookie, you can thank the woman behind them!

In honor of the remarkable women whose breakthroughs have advanced technology and the ease of our day to day lives, we're sharing the stories of twenty ingenious women whose inventions have changed the world. Whether they were scribbling designs two centuries ago or are still working today, these clever creators deserve to have their stories told. We've also included a few stories of modern-day Mighty Girls who have taken up the challenge of becoming the inventors of today — and tomorrow.

If you'd like to learn more about any of the featured women or introduce them to children and teens, where possible we're also sharing reading recommendations for both children and adults, as well as other resources that celebrate these innovative women.

For more stories of inspiring women, check out the other posts in our Mighty Girl Heroes blog series, Those Who Dared to Discover: 15 Women Scientists You Should Know, Spies, Medics, Soldiers, & Peacemakers: 15 Women Wartime Heroes You Should Know, and Guardians of the Planet: 10 Women Environmentalists You Should Know.

Women Inventors You Should Know

Jeanne Villepreux-Power (1794 - 1871)

Jeanne Villepreux-Power

Jeanne Villepreux-PowerAlthough the name Jeanne Villepreux-Power is little known now, the French naturalist was famous in her day for an invention that allowed people to study marine life more easily: the aquarium! Villepreux-Power started her scientific studies on the island of Sicily, and in 1832, she started investigating the paper nautilus. Popular opinion held that the nautilus took its shell from another organism, but in order to determine if this was true, she needed to be able to observe one closely. Villepreux-Power created the first glass aquarium so that she could observe the nautilus in controlled conditions, proving that it made its own shell. She went on to design two additional variants: a glass apparatus within a cage for studying shallow water creatures, and a cage-like aquarium that could be raised and lowered to different depths. For her groundbreaking work, Villepreux-Power became the first female member of the Catania Accademia, as well as over a dozen other scientific academies.

Margaret E. Knight (1838 - 1914)

Margaret "Mattie" Knight

Margaret "Mattie" KnightIf you've ever used a paper bag, you can thank Margaret "Mattie" Knight, the 19th century's most famous woman inventor! Born in York, Maine, Knight was most well-known for a machine she built when she was 30 which folded and glued paper to create a flat-bottomed paper bag. The product was popular — so popular, in fact, that a man stole the idea to patent himself. When Knight took him to court for patent interference, he argued that a woman "could not possibly understand the mechanical complexities." Knight won her case by providing proof that she had designed the machine, earning herself the right to patent her machine. Over the course of her career, Knight invented over 100 different machines and patented 20 of them, including a rotary engine, a shoe-cutting machine, and a window frame with a sash. But if the true test of an invention is its staying power, then Knight's paper bag — still used today — is proof of her incredible gifts.

Josephine Cochrane (1839 - 1913)

Josephine Cochrane" width="220" height="318" /> Josephine Cochrane

Josephine Cochrane" width="220" height="318" /> Josephine CochraneAmerican inventor Josephine Cochrane came up with the idea of a mechanical dishwasher — one that would hold dishes securely in a rack while the pressure of a water sprayer cleaned them — after servants chipped heirloom dishes. But when her husband died in 1883, leaving her with substantial debt, making the dishwasher work — and become profitable — became a necessity. She received her patent in 1886 and began marketing her dishwasher to hotels. "You cannot imagine what it was like in those days... for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone," she told one reporter. "I had never been anywhere without my husband or father — the lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn’t — and I got an $800 order as my reward." In 1893 her dishwasher was exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, making it into a household word. Cochrane continued selling her dishwasher until shortly before her death, and her legacy lives on: her company was bought by KitchenAid in 1916, and Cochrane is still listed as one of its founders.

Maria Beasley (1847 - 1904?)

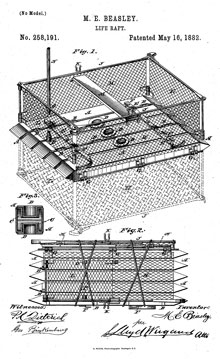

Maria Beasley's life raft design

Maria Beasley's life raft designAmerican inventor Maria Beasley made a fortune with one invention — and saved lives with another! Little is known about this remarkable woman today, but it is obvious that she was a dedicated entrepreneur; she successfully marketed at least 15 inventions, including a foot warmer, an anti-derailment device for trains, and a barrel-making machine that resulted in an estimated income of $20,000 a year at a time when most working women earned $3 a day. But in 1880, she invented something that would save lives at sea: a dramatically improved life raft. Although ships did have emergency rafts, they were simple planks with hollow floats and no guard rails — almost exactly like a raft made of wood a character might make in a cartoon. Beasley wanted to create a raft that was "fire-proof, compact, safe, and readily launched." By changing the style of the floats, she created a raft that could be folded for storage but unfolded quickly in an emergency, yet still allowed for guard rails at the sides. Despite her amazing accomplishments, however, the attitudes of her time are still obvious: in the 1880 US Census, Beasley was listed as an "unemployed housewife."

Mary Anderson (1866 - 1953)

Mary Anderson

Mary AndersonCan you imagine driving a car in bad weather without windshield wipers? Until Mary Anderson thought of them, that was the only option! Anderson was already a real estate developer and rancher when she visited New York City in 1902 and rode on a trolley car where the driver had to open the panes of the front window in order to see through falling sleet. As soon as she returned home to Alabama, she set to work conceiving a solution. Her device used a lever inside the vehicle to control a rubber blade on the windshield; similar devices had been made earlier, but Anderson's was the first effective model. Amazingly, car manufacturers initially didn't see the value in her invention; one Canadian firm declined her invention in 1905, saying "we do not consider it to be of such commercial value as would warrant our undertaking its sale." However, in 1922, Cadillac became the first car manufacturer to include a windshield wiper on all its vehicles, and after Anderson's patent expired, they quickly became standard equipment.

Sarah Breedlove / Madam C. J. Walker (1867 - 1919)

Sarah Breedlove, known as Madam C.J. Walker" width="220" height="311" />

Sarah Breedlove, known as Madam C.J. Walker" width="220" height="311" />

Sarah Breedlove was the first child of her family born after the Emancipation Proclamation — and she would go on to become the first female self-made millionaire in the United States! Married and widowed by the age of 20, she was working as a laundress when she realized that she, and many other black women, struggled with hair loss and scalp diseases due to a lack of indoor plumbing and harsh ingredients in hair products. Over several years, she developed her own line of hair care products specifically designed for African American hair, and branded them with her new identity as Madam C. J. Walker; the title was deliberately chosen to evoke Parisian luxury. When her line was ready for sale, she also set up a college to train "hair culturists," creating a new employment opportunity for thousands of African American women. As her wealth and influence grew, Madam Walker brought them to bear on social and political issues and made donations to African American schools, orphanages, and retirement homes. Her legacy, thought, is one of perseverance; she famously said, "If I have accomplished anything in life it is because I have been willing to work hard."

Melitta Bentz (1873 - 1950)

Melitta Bentz

Melitta BentzIf you like coffee, you can thank German entrepreneur Melitta Bentz for making it easier to brew! Bentz was a housewife when she became frustrated with the difficulty of making coffee: percolators often over-brewed it, the espresso-style machines of her day left grounds in the drink, and linen bag filters were extremely difficult to clean. After experimenting with multiple materials, she struck on the idea of using blotting paper from her son's school exercise book, nested inside a brass pot perforated with a nail; she got a patent and set up a business to manufacture her filters. Within a year, she was selling hundreds of her filters, including 1,200 at the 1909 Leipzig Fair alone, and by 1928 her company employed dozens of people. She continued to improve her filter over the years, making it increasingly popular. Bentz was beloved by her employees for her generous bonuses and work schedules, and she also created "Melitta Aid", a social fund for her company's workers. And if the name sounds familiar, don't be surprised: the Melitta Group is still making coffee, coffee makers, and filters today.

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 - 1973)

Beulah Louise Henry" width="220" height="314" /> Beulah Louise Henry

Beulah Louise Henry" width="220" height="314" /> Beulah Louise HenryA full list of Beulah Louise Henry's inventions would be a lengthy one — she's known for 110 inventions and 49 patents, and the American inventor profited from all of them. Henry submitted her first patent, for a vacuum ice cream freezer, while still a college student in 1912, and moved to New York City in 1924 to found two companies to sell her many inventions. In the 1930s and 1940s, she shifted her attention to improving existing machines, including typewriters; one of her patents, for a "protograph," was a typewriter that created and original and four identical copies without carbon paper. With her reputation as a professional inventor solidified, she spent the 1950s and part of the 1960s working for companies as a consultant, and when she died in 1973 she was remembered by all for her creativity and drive. Henry, however, would have argued that she didn't need drive to create so many inventions: "I invent," she said, "because I cannot help it."

Ruth Graves Wakefield (1903 - 1977)

Ruth Wakefield" width="220" height="281" /> Ruth Wakefield

Ruth Wakefield" width="220" height="281" /> Ruth WakefieldEvery single thing we use in a day had an inventor somewhere along the line — even the chocolate chip cookie! American entrepreneur Ruth Graves Wakefield was unusual for her time: she was a university graduate who began her career touring as a dietician to teach people about food and nutrition. In 1930, she and her husband bought the Toll House Inn, which quickly became famous for Wakefield's food, especially her desserts. However, Wakefield wanted to offer guests something different and new. She took an ice pick to a block of chocolate, added it to her cookie dough, and the chocolate chip cookie was born. When Wakefield reissued her best selling cookbook, she added the Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookie to the dessert section; it was so popular that chocolate company Nestle noticed a spike in demand for their semi-sweet chocolate, and approached Wakefield about the rights to the recipe. Soon Nestle was making semi-sweet chips specifically for cookies, and printing the Toll House cookie recipe on every box. And Wakefield got a sweet though minimally profitable payout — one dollar plus a lifetime supply of chocolate!

Grace Hopper (1906 - 1992)

Grace Hopper

Grace HopperAny time you type a command on your computer, you can thank programming pioneer Grace Hopper! The mathematician and US Navy reserve officer began her computer science career when all programs were written in numerical code. Hopper realized that programming would be more accessible if people could code in their own language; she invented the first compiler in 1952, essentially teaching computers to "talk." It took some time for her colleagues to realize that she had succeeded: "Nobody believed that...They told me computers could only do arithmetic." She later co-invented the COBOL computer language, the first universal programming language used in business and government. During Hopper's long career with the Navy — during which she achieved the rank of Rear Admiral by special Presidential appointment and was nicknamed "Amazing Grace" — she took particular pride in teaching: "The most important thing I've accomplished, other than building the compiler, is training young people," she said. "I keep track of them as they get older and I stir 'em up at intervals so they don't forget to take chances."

Virginia Apgar (1909 - 1974)

Virginia Apgar" width="220" height="283" /> Virginia Apgar

Virginia Apgar" width="220" height="283" /> Virginia ApgarAmerican doctor Virginia Apgar had a particularly noble motivation for her invention: protecting the health of newborn babies. Apgar was a pioneering anesthesiologist, the first female full professor at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, where she also conducted research at the affiliated Sloane Hospital for Women. She realized that medical personnel had no standardized way to assess the health of newborns, so she set out to develop a clear, quick set of criteria that were easy to understand and communicate. Her Apgar Score, which she first performed in 1953, used her last name as a mnemonic for areas to assess: Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration. Thanks to the Apgar Score, newborns who need urgent medical assistance can easily be identified. Apgar was also the author of a groundbreaking 1972 book, Is My Baby All Right?, which provided parents with a guide to birth defects — revolutionary in a time when they were a taboo topic. Her determination to care for both the women and the babies under her care is best summed up by this quote: "Nobody, but nobody, is going to stop breathing on me."

Hedy Lamarr (1914 - 2000)

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy LamarrShe was one of the most glamorous stars of the black and white film era — and she was also one of the minds behind an invention that provided the foundation for GPS, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi technology! Austrian-American actress Hedy Lamarr was also a gifted mathematician and engineer, and when World War II broke out, she wanted to make a contribution to the war effort by improving torpedo technology. Working with musician and composer George Antheil, Lamarr developed the idea of "frequency hopping," which could encrypt torpedo control signals, preventing enemies from jamming them and sending the torpedoes off course. Although Lamarr and Antheil were granted a patent for the idea in 1942, the US Navy ignored their technology for 20 years, finally putting it to use during a 1962 blockade of Cuba. Since then, though, Lamarr's spread-spectrum technology has become the foundation for the portable devices that we use every day, for which she was inducted into the National Inventor's Hall of Fame in 2014.

Marion Donovan (1917 - 1998)

Marian Donovan

Marian DonovanIf you think dealing with a baby's diapers is messy now, imagine what it was like before there were waterproof covers! When American entrepreneur Marion Donovan had children, she soon discovered that cloth diapers, which at the time had no covers, were extremely prone to leaks: she spent hours replacing and washing bedsheets and clothing. Using a shower curtain, she sewed a cover to go over the cloth diapers, which prevented leaks without causing chafing or diaper rash. By 1949, she had four patents for her "boater" diaper cover, including one that used plastic snaps rather than diaper pins, but her initial attempts to sell to manufacturers were unsuccessful, so she hired a company to make them for her and started selling them through Saks Fifth Avenue. Two years later, she sold her company and patents to the Keko Corporation for $1,000,000. Donovan went on to invent and patent 20 other items, all based on simplifying day-to-day tasks: the question she asked before coming up with an idea, she said, was "What do I think will help a lot of people and most certainly will help me?"

Mary Sherman Morgan (1921 - 2004)

Mary Sherman Morgan" width="220" height="279" /> Mary Sherman Morgan

Mary Sherman Morgan" width="220" height="279" /> Mary Sherman MorganWhen Mary Sherman Morgan decided to study science, she had no idea that her work would help make space race history! The American chemist left university to take a secret position for a munitions factory during World War II, improving explosives and ordinance for use at the front. When the war was over, she applied to work for North American Aviation's Rocketdyne Division, working on rocket propellants; out of 900 engineers, she was one of only a handful without a college degree — and the only woman. When NAA was contracted by the Jupiter missile project to design a better rocket fuel, Morgan was named the technical lead; she ended up creating Hydyne, which propelled the Jupiter rocket as it placed America's first satellite, Explorer 1, into orbit. Because so much of her work was classified, few people knew about her contributions until her son, George Morgan, wrote a play and a book about her life. In retrospect, he laughs remembering how he struggled as a child to launch home made rockets in the Arizona desert: "If I'd known how much expertise in rocketry my mother had, we could have asked her for help and saved ourselves a great deal of trouble."

Marie Van Brittan Brown (1922 - 1999)

Marie Van Brittan Brown" width="220" height="330" /> Marie Van Brittan Brown

Marie Van Brittan Brown" width="220" height="330" /> Marie Van Brittan BrownAmerican nurse Marie Van Brittan Brown was concerned about safety when she was home alone at odd hours of the day or night; the crime rate in her neighborhood in Queens, New York, had been increasing, and police response time was slow. She realized that she would feel less vulnerable if she could see who was at her door — without opening it. Working with her husband Albert, an electrician, Brown created a system of four peep holes and a movable camera that connected wirelessly to a monitor in their bedroom. A two-way microphone allowed conversation with someone outside, and buttons could sound an alarm or remotely unlock the door. The Browns received a patent for their security system in 1969, and Brown received an award from the National Science Committee for her truly innovative idea. Her idea became the groundwork for all modern home security systems, and she's also inspired many fellow inventors, including her own daughter, who also holds multiple patents.

Stephanie Kwolek (1923 - 2014)

Stephanie Kwolek" width="220" height="341" /> Stephanie Kwolek

Stephanie Kwolek" width="220" height="341" /> Stephanie KwolekChemist Stephanie Kwolek was working on an alternative for steel in radial car tires when she developed a fiber credited with saving thousands of lives: Kevlar. Born near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Polish immigrants, Kwolek originally planned to become a doctor, but after accepting a research position with DuPont in 1946 to save up for medical school, she discovered a passion for chemistry research that led to a 40 year career. She invented Kevlar in 1964 when an experiment with turning a solid polymer into a liquid didn't work as planned; while her peers considered the experiment a failure, Kwolek took a closer look, and discovered that fibers within the liquid were five times stronger than steel. Kevlar has since been used for everything from boots for firefighters to spacecraft parts, but it's most famous for its use in bulletproof body armor; since Kevlar vests were introduced in the 1970s, at least 3,000 police officers' lives have been saved, as well as those of countless soldiers and civilians in combat zones. In fact, on the same day that Kwolek died, DuPont announced the sale of the one millionth protective vest using her invention.

Jeanne L. Crews

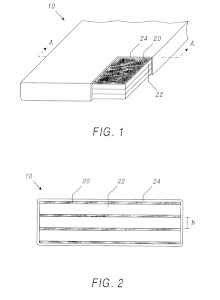

space bumper design" width="220" height="300" /> Jeanne L. Crews' space bumper design

space bumper design" width="220" height="300" /> Jeanne L. Crews' space bumper designAt a time when there were almost no women scientists at NASA, American engineer Jeanne L. Crews made a critical contribution: designing a "space bumper" that could protect satellites and manned craft from space debris and meteorites. After joining NASA in 1964, Crews realized that space vehicles would not hold up to impacts from even small objects. She wasn't alone in her concerns: another NASA employee, Burt Cour-Palais, was concerned about the same problem, so as soon as she met him, she declared, "We are going to go fix this problem." They disagreed on the best solution, so each chose an approach to pursue. Crews decided to work with a ceramic fabric called Nextel; she created a multi-layered, multi-fabric shield, lighter than a single sheet of aluminum but capable of stopping the vast majority of space debris by diffusing the object's energy as it penetrated the bumper's layers. Thanks to her determination and creativity, the astronauts of today — and the future — are a little bit safer as they travel the solar system.

Patricia Bath (b. 1942)

Patricia Bath

Patricia BathSince she entered the field of ophthalmology, Patricia Bath has been breaking new ground! She was the first black person to serve as an ophthalmology resident at New York University and the first woman on staff at the Jules Stein Eye Institute, but most importantly for this discussion, she was the first African-American female doctor to receive a patent for medical purposes. That patent was for the Laserphaco Probe, a medical device she invented in 1981 that quickly and painlessly uses a laser to dissolve cataracts in the eye, then irrigates and cleans the eye to make inserting a replacement lens quick and easy. The Laserphaco Probe is now used internationally as a quick and safe way to prevent blindness due to cataracts. She is also the inventor of a new discipline, community ophthalmology, which is dedicated to ensuring that all members of the population have access to eye and vision care. Even if people can't afford an operation, Bath believes that ophthalmologists should do all they can to care for their vision; after all, she says, "The ability to restore sight is the ultimate reward."

Anna Stork and Andrea Sreshta

Andrea Sreshta" width="220" height="241" /> Anna Stork and Andrea Sreshta

Andrea Sreshta" width="220" height="241" /> Anna Stork and Andrea SreshtaAnna Stork and Andrea Sreshta were graduate students at Columbia University's School of Architecture when the devastating earthquake hit Haiti in 2010; in one of their classes, they were assigned a project to find a way to help with disaster relief. After speaking to a relief worker, Stork and Sreshta realized that there was an often-forgotten need after disasters strike: light. The pair decided to create an inflatable, waterproof, and solar-powered light, the LuminAID Solar Light. Their design can be packed flat, charges in 6 hours to provide light for 16, and even features a handle to make it easy to carry. They used a crowdfunding campaign to make their first 1,000 lights, and after LuminAID became a favorite with outdoor enthusiasts — and in home emergency kits — they started a Give Light Project: one light is donated for every light purchased. They have since provided lights to Nepal and to Syrian refugees. Thanks to the work of these two creative innovators, more people will have access to the gift of light during the darkest of times.

Anna and Andrea's LuminAid Solar Light is now available on Amazon in a LuminAid Single Pack or Double Pack.

Ayla Hutchinson

Ayla Hutchinson

Ayla HutchinsonAfter New Zealand teen Ayla Hutchinson saw her mother cut her finger while splitting kindling with a hatchet, she realized that there had to be a better way to get this critical job done. As a science fair project, she decided to invent a device that made it easier and safer to cut kindling. The result is the Kindling Cracker, a cast-iron device that uses a built-in axe blade in a safety cage: the cage holds the wood while you hit it with a hammer, easily splitting the log in pieces. She received such a positive response to her prototype that she developed the idea further, and her father helped her found a company to manufacture it; two years later, she estimates that there are tens of thousands of Kindling Crackers in use across New Zealand. Equally exciting was a 2015 distribution agreement with a major US tool company, which has already received and sold 22 tons of Kindling Crackers in North America. For Ayla, though, the best part is knowing she's helping people: "It also gives people with disabilities or physical impairments the freedom to cut their own kindling again.... It makes it easier and safer for everyone to cut kindling."

To learn more or order Ayla's invention on Amazon, visit the Kindling Cracker.

Komentar

Posting Komentar